So let's briefly talk about Canto Bight, the casino planet where the new character Rose and Finn visit on a side mission. Obviously one of the weaknesses of this sub plot is that it is profoundly unsuccessful. Rose and Finn do not make contact with the person they are supposed to find, and as a result the entire plan is a failure.

What was actually lost, however, is something musch more important. The one thing that needed to happen at this point in the oveall story is that we needed a moment when the main characters are adventuring together, when they learn about each others strengths and weaknesses, where they learn to trust one another and where they form the backbone of the team that will eventually rise in importance to face the ultimate evil.

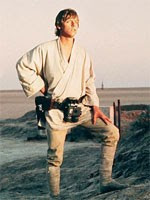

In Empire Strikes Back, this was the long journey escaping from the Imperial ships where Han and Leia hide in the asteroid belt, where they escape from the asteroid worm, where they escape from the star destroyers by pretending to be space debris. "You do you have your moments," says Leia. "You may not have many of them, but you do have them." This is a key establishing scene where we all recognize that Han really is an accomplished pilot and smuggler. He's not just a lightweight who's all talk, like we think in the begining when he's bragging to Obi-wan in Mos Eisley. And more than that, we identify Han, Chewie, and Leia as a force to be reckoned with; as an effective team full of resourcefulness, cunning and strategy. Later, when we see them attacking the shield base on the Endor moon, we already know that they bring some competency to the table.

Now, here's the problem. We need a similar moment in this trilogy as well. This canto bight scene was the moment when we had Finn and Poe go off and have adventures together and we see them learn to trust one another, and we demonstrate their competence as heroes. Maybe everything doesn't go as planned, but they come out of it as a team and they grow in stature not only as part of the Resistance, but also in the eyes of the audience as well.

Except that none of this happens. This was the reality of what was missed by framing that scene as we did. Rian Johnson said that he originally wrote that scene for Fin and Poe. Later, he changed it to better match the ethos of the film, introducing Rose instead. What we sacrificed, though, is that we lost the team-building moment between Fin and Poe. Right now, they seem fundamentally unrelated to one another. Previously, Fin went off with Han Solo to Starkiller base, and Fin and Poe haven't crossed paths in any meaningful way since the opening scene of Force Awakens, so we haven't established that they really know or like or trust one another. Certainly after the Canto Bight fiasco, Poe has even less reason to trust Fin's capabilities than he had before.

And the truth is that neither does the audience. Everything that Fin and Rose attempted, from parking the ship, to contacting the slicer, to escaping on horseback, all of it was a failure and ultimately pointless. Even the audience, who are wholeheartedly behind Fin, really don't know what strength he brings to the table. What is his competency that makes him valuable to the Resistance? This was the story's chance to demonstrate it for the sake of the audience and the narrative. Instead, we demonstrate his incompetence.

This same opportunity was present for Rose, as well. I enjoyed Rose as a new character, and recognize that character type from anime stories: the un-glamorous and slightly annoying but loyal sidekick. But even though I like her, I still don't know what Rose brings to the table. The same ambiguity that Fin struggles with is a problem with Rose's character as well. Is she part of the team, with Fin and Poe? The story is unclear. The problem is that the story didn't set up enough hooks to tie Rose into the greater story line. Rather than wondering with breathless speculation about how Rose might develop in the next movie, the audience wouldn't be surprised if we never hear about Rose again. That's how little hinges on her character. Is Rose a Lando figure, or is that DJ? At this point, we shouldn't be guessing. But literally nothing else about Rose is interesting in any way, and her presence doesn't set in motion any plot premise or suggest any payoff for the final movie in this trilogy.

And this is the larger problem with the trilogy as a whole. At this point in the trilogy, we should be thoroughly introduced to these new characters and ready to hand off the narrative from the old guard to the young heroes. But currently, Rose is a dead end, in a movie where we should be establishing plot arcs and giving each of our principal characters motivations. At this point, each of them is a blank slate, one the Last Jedi has carefully scrubbed clean.

Friday, December 29, 2017

Wednesday, December 20, 2017

The Last Jedi part 2

So I just want to look very briefly at the bigger picture about where Last Jedi fits into the broader landscape. It is a tragedy in three acts.

Act One. In the late '70s Lucas has a vision of bringing to the big screen a heady mix of four key components:

The resulting storytelling was electrifying in the way that it energized the imaginations of the audience. Over the course of the trilogy, each of those elements was faithfully preserved and expanded.

It's easy to forget, or underestimate, the impact that Star Wars had on its fans, during the 80s. Fans all over the US were literally camped out in front of theaters for days waiting in line to get be the first to get into theaters on opening night. And the reason they were there was unique to Star Wars. Something about the seriousness with which Star Wars treated its subject material spoke to science fiction fans. Star Wars captured the nobility and heroism of the best adventure story, but coupled it with credible and realistic sets and special effects, a combination that wasn't really present in original Star Trek or the other science fiction films of the day. There had been campy teen films, and the bizarre 2001: a space oddessy, but the perfect combination of heroic adventure and technical filmmaking was elusive until Star Wars was released.

Act Two. In the late '90s Lucas returned to dust off the franchise and make a canonical trilogy once again. Once again he used the successful combination of science fiction and fantasy, but this time he began to stretch the third pillar when he explored the order of ancient knights called the Jedi. And he seemed to abandon the stark contrast between good and evil.

This second trilogy was less well received, due in large part to some directorial and narrative sloppiness on Lucas' part. More detrimental to the narrative, though, was that rather than focusing on the struggle between good and evil, we became embroiled in semi-evil trade disputes and the moral ambiguity of Separatists vs the Republic.

This second trilogy was less well received, due in large part to some directorial and narrative sloppiness on Lucas' part. More detrimental to the narrative, though, was that rather than focusing on the struggle between good and evil, we became embroiled in semi-evil trade disputes and the moral ambiguity of Separatists vs the Republic.

It was largely acknowledged that the Prequel trilogy was not as good as the Original trilogy. The news that a new trilogy was being made after the hiatus of over a decade had left original fans giddy with anticipation, but their soaring enthusiasm only served to deepen the eventual disappointment. Tightly focused stories of the original trilogy gave way to endless light saber duels and pointless mass battles

Act Three. It was with a wary sense of hope that Star Wars fans learned of the transfer of control from Lucas himself to Disney. Finally, they thought the lack of Lucas' self-indulgence would get the franchise back on track and open it up to more stories in the vein of the Original Trilogy.

The first installment of the new trilogy, Force Awakens seemed to make good on this promise. It introduced a new cast of young Rebels to fight the malevolent First Order, and gave homage to the four pillars of the original series: hard science fiction in the form with new worlds and a giant Star Killer base, a mystic Force that called to Rey in newly discovered powers and visions, a shadowy figure of the legendary Luke Skywalker whose discovery would potentially lead to continuing the Jedi traditions in Rey, and finally an evil mirror in the dark side Snoke and his reckless apprentice Kylo Ren.

While some complained about obvious parallels with Episode IV, it was largely welcomed as a return to the storytelling of Star Wars' glory years. One of the most powerful thing that Force Awakens accomplished was that it got the Star Wars fans engaged with the story again. The audience began to identify with the characters in a way that it hadn't throughout the prequels. They began to become attached to the struggles of Poe and Finn, began to develop a healthy awe for the emergent Force powers of Rey. And it was this identification with the characters, coupled with the obvious leading of FA director Abrams, that led to speculation about past history and future developments.

Once again the audience was longing for (rather than dreading) the next episode's release, wondering where the story will lead. This was far different from the dark years during the prequel trilogy, where the audience was dreading, rather than anticipating, the next installment, wondering instead how badly it would break cherished icons, how cringe-worthy the next Anakin-Padme interaction would be; wondering when the next major character would be Jar-Jarred. This was a fandom that was keeping its source material at arms length like an angry cat, never knowing when it would purr or scratch.

The disservice that Last Jedi did to the fans was that just when they though it was safe to invest in the story again, that it was safe to grow attached to the main characters again, Episode 8 made them go through it all over again. It was like an abusive boyfriend seduced us back and then immediately beat us up. And then, after it was over, began to gaslight us that it never happened, and that we're to blame for clinging to nostalgia.

So you know what I'm NOT looking forward to? I'm NOT looking forward to the single movie next year. I have no desire to see how badly they are going to screw up the character of Han Solo. They've already turned him from being a competent and dangerous smuggler who doesn't turn his back on his friends, to a deadbeat incompetent, inept charlatan who can't keep his life together and who ran out on his wife and abandoned his son when things got rough.

That's what they've already done to him. Can you imagine what revisionism and ret-conning is going to happen when they get their fingers into his backstory? Just for comparison, look what they did to Luke. Does anyone doubt that something much darker and more unseemly awaits Han?

And while I'm thinking about it, I have no desire to see what Rian Johnson does with an entire Trilogy on his own. I'm not saying that I'm rage quitting the franchise and that Star Wars is dead to me. I'm just saying that I'm back to keeping the franchise at arms length again. This is probably not an opening night kind of relationship, anymore. And, sadly, I think that is exactly where the show runners want us to be.

Act One. In the late '70s Lucas has a vision of bringing to the big screen a heady mix of four key components:

- Hard science fiction. By this I mean, a populated galaxy with multiple inhabited planets and many diverse alien species. Space ships and blaster pistols, robots and androids.

- A fantasy mythos with a powerful Force that allowed its practitioners seemingly magical powers not only to move things but to have visions and intuit the future.

- A mystic order of ancient knights and their apprentices bound by a code of honor and family lineage and opposing a depraved and twisted mirror of itself in the Sith.

- A central conflict between good and evil, between the black of Vader and Palpatine and the white of Princess Leia and Luke. With the freedom-loving, underdog Rebels facing impossible odds against an evil Empire and eventually triumphing.

The resulting storytelling was electrifying in the way that it energized the imaginations of the audience. Over the course of the trilogy, each of those elements was faithfully preserved and expanded.

It's easy to forget, or underestimate, the impact that Star Wars had on its fans, during the 80s. Fans all over the US were literally camped out in front of theaters for days waiting in line to get be the first to get into theaters on opening night. And the reason they were there was unique to Star Wars. Something about the seriousness with which Star Wars treated its subject material spoke to science fiction fans. Star Wars captured the nobility and heroism of the best adventure story, but coupled it with credible and realistic sets and special effects, a combination that wasn't really present in original Star Trek or the other science fiction films of the day. There had been campy teen films, and the bizarre 2001: a space oddessy, but the perfect combination of heroic adventure and technical filmmaking was elusive until Star Wars was released.

Act Two. In the late '90s Lucas returned to dust off the franchise and make a canonical trilogy once again. Once again he used the successful combination of science fiction and fantasy, but this time he began to stretch the third pillar when he explored the order of ancient knights called the Jedi. And he seemed to abandon the stark contrast between good and evil.

This second trilogy was less well received, due in large part to some directorial and narrative sloppiness on Lucas' part. More detrimental to the narrative, though, was that rather than focusing on the struggle between good and evil, we became embroiled in semi-evil trade disputes and the moral ambiguity of Separatists vs the Republic.

This second trilogy was less well received, due in large part to some directorial and narrative sloppiness on Lucas' part. More detrimental to the narrative, though, was that rather than focusing on the struggle between good and evil, we became embroiled in semi-evil trade disputes and the moral ambiguity of Separatists vs the Republic.It was largely acknowledged that the Prequel trilogy was not as good as the Original trilogy. The news that a new trilogy was being made after the hiatus of over a decade had left original fans giddy with anticipation, but their soaring enthusiasm only served to deepen the eventual disappointment. Tightly focused stories of the original trilogy gave way to endless light saber duels and pointless mass battles

Act Three. It was with a wary sense of hope that Star Wars fans learned of the transfer of control from Lucas himself to Disney. Finally, they thought the lack of Lucas' self-indulgence would get the franchise back on track and open it up to more stories in the vein of the Original Trilogy.

The first installment of the new trilogy, Force Awakens seemed to make good on this promise. It introduced a new cast of young Rebels to fight the malevolent First Order, and gave homage to the four pillars of the original series: hard science fiction in the form with new worlds and a giant Star Killer base, a mystic Force that called to Rey in newly discovered powers and visions, a shadowy figure of the legendary Luke Skywalker whose discovery would potentially lead to continuing the Jedi traditions in Rey, and finally an evil mirror in the dark side Snoke and his reckless apprentice Kylo Ren.

While some complained about obvious parallels with Episode IV, it was largely welcomed as a return to the storytelling of Star Wars' glory years. One of the most powerful thing that Force Awakens accomplished was that it got the Star Wars fans engaged with the story again. The audience began to identify with the characters in a way that it hadn't throughout the prequels. They began to become attached to the struggles of Poe and Finn, began to develop a healthy awe for the emergent Force powers of Rey. And it was this identification with the characters, coupled with the obvious leading of FA director Abrams, that led to speculation about past history and future developments.

Once again the audience was longing for (rather than dreading) the next episode's release, wondering where the story will lead. This was far different from the dark years during the prequel trilogy, where the audience was dreading, rather than anticipating, the next installment, wondering instead how badly it would break cherished icons, how cringe-worthy the next Anakin-Padme interaction would be; wondering when the next major character would be Jar-Jarred. This was a fandom that was keeping its source material at arms length like an angry cat, never knowing when it would purr or scratch.

The disservice that Last Jedi did to the fans was that just when they though it was safe to invest in the story again, that it was safe to grow attached to the main characters again, Episode 8 made them go through it all over again. It was like an abusive boyfriend seduced us back and then immediately beat us up. And then, after it was over, began to gaslight us that it never happened, and that we're to blame for clinging to nostalgia.

So you know what I'm NOT looking forward to? I'm NOT looking forward to the single movie next year. I have no desire to see how badly they are going to screw up the character of Han Solo. They've already turned him from being a competent and dangerous smuggler who doesn't turn his back on his friends, to a deadbeat incompetent, inept charlatan who can't keep his life together and who ran out on his wife and abandoned his son when things got rough.

That's what they've already done to him. Can you imagine what revisionism and ret-conning is going to happen when they get their fingers into his backstory? Just for comparison, look what they did to Luke. Does anyone doubt that something much darker and more unseemly awaits Han?

And while I'm thinking about it, I have no desire to see what Rian Johnson does with an entire Trilogy on his own. I'm not saying that I'm rage quitting the franchise and that Star Wars is dead to me. I'm just saying that I'm back to keeping the franchise at arms length again. This is probably not an opening night kind of relationship, anymore. And, sadly, I think that is exactly where the show runners want us to be.

Monday, December 18, 2017

The Last Jedi

So this is my initial reaction to seeing Star Wars The Last Jedi on Friday night. I'm sure that my impressions of the film will change over time and as I see it over again. I know that's true because I've already expreinced a shifting of my responses even during the few days since watching it, and I suspect that process to continue for at least several weeks.

Initiall, as I left the theater, I had a positive reaction to the movie. If someone were to ask me my opinion as I left the theater I would have said that, while I had some specific concerns, overall I enjoyed the movie. But only two days later, I'm feeling very dissatisfied.

I want to get the major concerns out into the open first.

1. No Golden Narrative Thread.

One of my greatest concerns is with the way that this trilogy is being handled. No one seems to be exerting narrative control over the trilogy. It is as if the two directors were at war with one another over the direction of the trilogy, and indeed, of the direction of the new Star Wars franchise. Even if we didn't appreciate all the directorial blunders of George Lucas' prequels, at least George had an artistic focus that was consistent about the Force, and about the nature of good and evil in the universe.

I say this because JJ Abrams laid out very specific narrative elements in the first movie, The Force Awakens, that weren't simply ignored in the second of the series, but were actively dismissed. It is as if Rian Johnson went out of his way to take the plot points that Abrams laid out as important and to dismiss them arbitrarily, or even to mock the audiences expectations of an answer.

A classic example of this was the character of Snoke, the arch bad guy behind Kylo Ren in Force Awakens (FA). He was effectively presented as an evil and power-hungry leader of the First Order, with a mysterious origin and a shadowy influence over Kylo's turn to the Dark Side. There was a wealth of potential story to be mined there and it encouraged fan speculation in the intervening two years between installments. Instead, however, Rian Johnson ignored it all and summarily killed Snoke in the middle act of Last Jedi (LJ) without any explanation whatsoever.

Similarly, Abrams carefully introduced the mystery of Rey's parents: who they were, and why she was left on Jakkuu. In fact, it was one of the defining beats in Rey's character arc; she spent the entire first episode searching for her place in the galaxy. In LJ, Rian decides to deal with this question by saying that it wasn't important. Rey's parents were nobodies, and she was basically alone in the universe.

The problem here is not that Ray's parents weren't notable, or that Snoke was a minor Sith. It is that the first of the trilogy insisted that these were important narrative questions that the story would answer, in much the same way that Luke's parents and Palpatine's rise to power were important in the first trilogy. As with all narrative seeds, they were promises to the listener that there would be a payoff in the end that will complete the narrative arc and reward the audience. The cycle of promise and payoff is the ultimate contract that the storyteller makes with the audience, and in this case all it led to was broken promises.

2. Contempt for Traditional Star Wars Themes

It was as if Rian Johnson treated with disdain many of the elements that he inherited when he agreed to direct the second film. And this is the second major problem that I had with Last Jedi. The quintessential elements that define the Star Wars universe were treated with almost violent contempt.

Luke Skywalker, the hero of A New Hope, was now a washed up old drunk living under a bridge, drunk on his failure and living out his life as an anti-social hermit. Rather than retreating from the struggles of the Rebel Alliance to discern some greater enlightenment, Luke was cowardly and self-loathing, having abandoned the Force and his responsibility as a Jedi.

I felt as though Rian took delight in taking this noble-hearted paladin of the Jedi Order, the defenders of goodness, a guardian of peace and justice in the Old Republic, and seeing how far down into depravity he could crush him. It seems common in Hollywood to treat with contempt struggles between good and evil. They are derided as being trite and simplistic. Luke's fall from grace makes him more complicated, more interesting in Rian's eyes.

It seems that Johnson is not alone in that, because Han is also transformed from a fearless and inventive smuggler living life on the edge, into a deadbeat dad, someone who can't handle married life and runs out on his son. This vision of Han as a cheat and swindler is far different from the character we left as General of the Endor assault. All the ground that the character had gained during his arc in the original trilogy had been squandered and abandoned by the time of Force Awakens. Similarly, Leia here is a tired old soul, struggling to hold the rebellion together as her allies slip between her fingers.

3. The Failed Transfer of Leadership

While the first of the trilogy had to re-work some old ground to reclaim the disillusioned Star Wars fans, this second installment needed to be all about the transition to the new heroes, to Rey, Finn, and Poe. Relegated, somewhat, to the background in Force Awakens behind the larger-than-life presence of Han Solo and Chewbacca, this was the moment for Poe and Finn to shine.

Instead, Rian Johnson purposefully went out of his way to diminish the impact that these characters had on the plot of Last Jedi. Poe spent the entire time trapped on board the Resistance command ship, being an uncharacteristic jerk to Leia and Holdo. For his part, Finn got to leave the ship on a spectacularly unsuccessful mission that he botched almost from the jump, and that had zero impact on any major plot development.

The problem with Canto Bight is that it didn't allow Finn to develop any core competency, something that the ace pilot Poe Dameron already possessed in abundance. Action/adventure stories are about character's competencies, while Dramas are about character's weaknesses. Part of what the audience is struggling with is that we were expecting an action-adventure film, when the directors actually intended to give us a drama/soap opera.

I felt that Finn and Rose were a great pairing, its just that neither of the two were particularly competent at anything, and both together were singularly unsuccessful in completing their mission. I didn't dislike the sortie to Canto Bight, but it was so pointless that it's hard to argue that it led to any particular character development in Finn.

Ultimately, this prevented these characters from taking center stage during this key transition. I would like to say that Poe developed as a character from the overly aggressive cockpit jockey to a commander more worthy of leadership. And that Finn moved from having a tendency to run from trouble, to someone who was willing to go out on a limb to help his side. The truth, however, was that Finn had already covered this ground in Force Awakens, and to find him running away again in this movie was an unjustified move backward. Finn had already learned this lesson.

Similarly, Poe was already a good leader, and we needed to introduce this flaw in his character in order for us to have something to fix.

Continue to Part II

Initiall, as I left the theater, I had a positive reaction to the movie. If someone were to ask me my opinion as I left the theater I would have said that, while I had some specific concerns, overall I enjoyed the movie. But only two days later, I'm feeling very dissatisfied.

I want to get the major concerns out into the open first.

1. No Golden Narrative Thread.

One of my greatest concerns is with the way that this trilogy is being handled. No one seems to be exerting narrative control over the trilogy. It is as if the two directors were at war with one another over the direction of the trilogy, and indeed, of the direction of the new Star Wars franchise. Even if we didn't appreciate all the directorial blunders of George Lucas' prequels, at least George had an artistic focus that was consistent about the Force, and about the nature of good and evil in the universe.

I say this because JJ Abrams laid out very specific narrative elements in the first movie, The Force Awakens, that weren't simply ignored in the second of the series, but were actively dismissed. It is as if Rian Johnson went out of his way to take the plot points that Abrams laid out as important and to dismiss them arbitrarily, or even to mock the audiences expectations of an answer.

A classic example of this was the character of Snoke, the arch bad guy behind Kylo Ren in Force Awakens (FA). He was effectively presented as an evil and power-hungry leader of the First Order, with a mysterious origin and a shadowy influence over Kylo's turn to the Dark Side. There was a wealth of potential story to be mined there and it encouraged fan speculation in the intervening two years between installments. Instead, however, Rian Johnson ignored it all and summarily killed Snoke in the middle act of Last Jedi (LJ) without any explanation whatsoever.

Similarly, Abrams carefully introduced the mystery of Rey's parents: who they were, and why she was left on Jakkuu. In fact, it was one of the defining beats in Rey's character arc; she spent the entire first episode searching for her place in the galaxy. In LJ, Rian decides to deal with this question by saying that it wasn't important. Rey's parents were nobodies, and she was basically alone in the universe.

The problem here is not that Ray's parents weren't notable, or that Snoke was a minor Sith. It is that the first of the trilogy insisted that these were important narrative questions that the story would answer, in much the same way that Luke's parents and Palpatine's rise to power were important in the first trilogy. As with all narrative seeds, they were promises to the listener that there would be a payoff in the end that will complete the narrative arc and reward the audience. The cycle of promise and payoff is the ultimate contract that the storyteller makes with the audience, and in this case all it led to was broken promises.

2. Contempt for Traditional Star Wars Themes

It was as if Rian Johnson treated with disdain many of the elements that he inherited when he agreed to direct the second film. And this is the second major problem that I had with Last Jedi. The quintessential elements that define the Star Wars universe were treated with almost violent contempt.

Luke Skywalker, the hero of A New Hope, was now a washed up old drunk living under a bridge, drunk on his failure and living out his life as an anti-social hermit. Rather than retreating from the struggles of the Rebel Alliance to discern some greater enlightenment, Luke was cowardly and self-loathing, having abandoned the Force and his responsibility as a Jedi.

I felt as though Rian took delight in taking this noble-hearted paladin of the Jedi Order, the defenders of goodness, a guardian of peace and justice in the Old Republic, and seeing how far down into depravity he could crush him. It seems common in Hollywood to treat with contempt struggles between good and evil. They are derided as being trite and simplistic. Luke's fall from grace makes him more complicated, more interesting in Rian's eyes.

It seems that Johnson is not alone in that, because Han is also transformed from a fearless and inventive smuggler living life on the edge, into a deadbeat dad, someone who can't handle married life and runs out on his son. This vision of Han as a cheat and swindler is far different from the character we left as General of the Endor assault. All the ground that the character had gained during his arc in the original trilogy had been squandered and abandoned by the time of Force Awakens. Similarly, Leia here is a tired old soul, struggling to hold the rebellion together as her allies slip between her fingers.

3. The Failed Transfer of Leadership

While the first of the trilogy had to re-work some old ground to reclaim the disillusioned Star Wars fans, this second installment needed to be all about the transition to the new heroes, to Rey, Finn, and Poe. Relegated, somewhat, to the background in Force Awakens behind the larger-than-life presence of Han Solo and Chewbacca, this was the moment for Poe and Finn to shine.

Instead, Rian Johnson purposefully went out of his way to diminish the impact that these characters had on the plot of Last Jedi. Poe spent the entire time trapped on board the Resistance command ship, being an uncharacteristic jerk to Leia and Holdo. For his part, Finn got to leave the ship on a spectacularly unsuccessful mission that he botched almost from the jump, and that had zero impact on any major plot development.

The problem with Canto Bight is that it didn't allow Finn to develop any core competency, something that the ace pilot Poe Dameron already possessed in abundance. Action/adventure stories are about character's competencies, while Dramas are about character's weaknesses. Part of what the audience is struggling with is that we were expecting an action-adventure film, when the directors actually intended to give us a drama/soap opera.

I felt that Finn and Rose were a great pairing, its just that neither of the two were particularly competent at anything, and both together were singularly unsuccessful in completing their mission. I didn't dislike the sortie to Canto Bight, but it was so pointless that it's hard to argue that it led to any particular character development in Finn.

Ultimately, this prevented these characters from taking center stage during this key transition. I would like to say that Poe developed as a character from the overly aggressive cockpit jockey to a commander more worthy of leadership. And that Finn moved from having a tendency to run from trouble, to someone who was willing to go out on a limb to help his side. The truth, however, was that Finn had already covered this ground in Force Awakens, and to find him running away again in this movie was an unjustified move backward. Finn had already learned this lesson.

Similarly, Poe was already a good leader, and we needed to introduce this flaw in his character in order for us to have something to fix.

Continue to Part II

Narrative Threads

Storytelling is about setting in motion narrative threads or arcs. It is about the balancing of promise with payoff.

Whenever you introduce a question in to the narrative, you are making a promise to the audience that if they invest in this promise, the story will reward them before its all done. The story will pay off that promise with a reward of insight or enlightenment.

This is why plot holes are so unbalancing to a story. Each one is an example of a broken promise.

Failed stories add on too many promises, and then fail to resolve them. They make flat characters whose potential is wasted. Their authors get distracted by a new idea and abandon previous promises and make a bunch of new ones. And sometimes storytellers simply have possibility-laden promises with disappointing payoffs.

Whenever you introduce a question in to the narrative, you are making a promise to the audience that if they invest in this promise, the story will reward them before its all done. The story will pay off that promise with a reward of insight or enlightenment.

This is why plot holes are so unbalancing to a story. Each one is an example of a broken promise.

Failed stories add on too many promises, and then fail to resolve them. They make flat characters whose potential is wasted. Their authors get distracted by a new idea and abandon previous promises and make a bunch of new ones. And sometimes storytellers simply have possibility-laden promises with disappointing payoffs.

Thursday, December 14, 2017

What is Story?

It's time to get a few definitions out of the way. I've been talking about story structure, and reviewing some easy story examples from popular TV shows, all without laying down a concrete understanding of what a story is. All that stuff that your sophomore English class made so incredibly boring is actually a little bit interesting when applied to something other than East of Eden, or A Room with a View or another book you were force to read because it was good for you

Also, people who have taught English pedagogy in the last 30 years are all incredible stuffed shirts who got a lot of stuff just wrong. There's no more charitable way to describe the horrible wreckage that they have made of discussing storytelling, a topic that should be fun and enlightening and invigorating, and should make you want to read more, to see more plays and movies and discuss them with your friends.

So lets get started with a few simple building blocks, on which most discussions rest.

1. What is a story?

This should have an easy answer, and it does, but so many people try to torture this into something that fits their pet theories that it becomes hard to understand. Here it is: a story takes a character and places it within a setting, from which a conflict emerges that is first developed and then resolved.

From this definition, you can see that a story is a very particular thing; it's not just an assemblage of words meant to entertain. Take away the character, for example, and you could have an entertaining piece of prose, but it would no longer be a story. The same is true for any of the story components; you can't have a story without a resolution, or a conflict. These could be informative and worthwhile but they aren't a story.

And this is actually the common definition that most people refer to, even unconsciously, when they think of a story. We're not talking about artificial constructs like rising action or denouement. When someone says, "Tell me a story." this is what they are most likely referring to. And this pattern is what will bring them the most satisfaction, whether that is a story shared around the dinner table or an action adventure movie seen in a theater.

A story incorporates specific elements including tone, theme, plot, crisis, etc. It uses these tools while filling the fundamental requirements.

2. What is a narrative?

So what do you call something that doesn't meet this simple criteria? Typically you refer to it simply as a narrative. A narrative is any passage of text, so its a much broader category. So for example an author writes a book that turns out to be mostly descriptive passages of the setting. There's nothing wrong with that, it simply isn't a story. Moby Dick, for example, spends long passages in describing the workings of a whaling ship, when no actual story is being told. It is only after this "setting" is carefully described that Melville gets around to his story about the sea captain and the whale.

3. What is a plot?

The plot is the series of events that happen throughout the course of the story. That's it; nothing more complicated than that. There was a time when English teachers talked about chronological sequences or how some events could be relayed out of chronological order, but all that is mostly nonsense. A plot can be constructed in or out of chronological order, it's all the same. Each is a viable option

In the same vein, we used to talk about a plot as only being an unbroken chain of cause and effect. But that isn't strictly required, either. Many events occur that weren't caused by the previous event and yet they are an integral part of the plot. However, the events are often tied together in some way.

Similarly, we used to talk abut plot in terms of exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, resolution. But the truth is that this concept is a bit misleading because it makes everything seem to be equally important, and equally long. The rising action is usually far more important and far longer than the falling action, so the mountain-like diagram doesn't represent a story very well at all. But it's another attempt at grappling with what might be an overly difficult concept.

4. Why look at this stuff, anyway?

So I've presented simple definitions, and talked about older concepts that aren't strictly observed anymore. Why bother?

The answer is that these are the markers we use to analyze a story. And they can help us figure out why a story might be more or less satisfying, which is the ultimate analysis of why a movie was good or bad.While those "rules" aren't strictly required, the choices that authors make concerning them are all very interesting.

For example, you might watch a movie and realize that it doesn't contain the basic requirements for a story. For example, the conflict that arose in the beginning of the story might not be the conflict that is resolved in the end. Or a story might switch main characters halfway through the narrative.

A very skillful author might get away with this and the story might still be a success, but if you come away with a nagging feeling of dissatisfaction, these are the first places you might check. And really that's the main reason for considering them at all. If a story likes to play fast and loose with the plot, if it tries to skim over characterization, those are warning signs. They don't mean that the story is doomed to failure, and authors take chances all the time with structure. But these are going to be some of the first places that we look.

Also, people who have taught English pedagogy in the last 30 years are all incredible stuffed shirts who got a lot of stuff just wrong. There's no more charitable way to describe the horrible wreckage that they have made of discussing storytelling, a topic that should be fun and enlightening and invigorating, and should make you want to read more, to see more plays and movies and discuss them with your friends.

So lets get started with a few simple building blocks, on which most discussions rest.

1. What is a story?

This should have an easy answer, and it does, but so many people try to torture this into something that fits their pet theories that it becomes hard to understand. Here it is: a story takes a character and places it within a setting, from which a conflict emerges that is first developed and then resolved.

From this definition, you can see that a story is a very particular thing; it's not just an assemblage of words meant to entertain. Take away the character, for example, and you could have an entertaining piece of prose, but it would no longer be a story. The same is true for any of the story components; you can't have a story without a resolution, or a conflict. These could be informative and worthwhile but they aren't a story.

And this is actually the common definition that most people refer to, even unconsciously, when they think of a story. We're not talking about artificial constructs like rising action or denouement. When someone says, "Tell me a story." this is what they are most likely referring to. And this pattern is what will bring them the most satisfaction, whether that is a story shared around the dinner table or an action adventure movie seen in a theater.

A story incorporates specific elements including tone, theme, plot, crisis, etc. It uses these tools while filling the fundamental requirements.

2. What is a narrative?

So what do you call something that doesn't meet this simple criteria? Typically you refer to it simply as a narrative. A narrative is any passage of text, so its a much broader category. So for example an author writes a book that turns out to be mostly descriptive passages of the setting. There's nothing wrong with that, it simply isn't a story. Moby Dick, for example, spends long passages in describing the workings of a whaling ship, when no actual story is being told. It is only after this "setting" is carefully described that Melville gets around to his story about the sea captain and the whale.

3. What is a plot?

The plot is the series of events that happen throughout the course of the story. That's it; nothing more complicated than that. There was a time when English teachers talked about chronological sequences or how some events could be relayed out of chronological order, but all that is mostly nonsense. A plot can be constructed in or out of chronological order, it's all the same. Each is a viable option

In the same vein, we used to talk about a plot as only being an unbroken chain of cause and effect. But that isn't strictly required, either. Many events occur that weren't caused by the previous event and yet they are an integral part of the plot. However, the events are often tied together in some way.

Similarly, we used to talk abut plot in terms of exposition, rising action, climax, falling action, resolution. But the truth is that this concept is a bit misleading because it makes everything seem to be equally important, and equally long. The rising action is usually far more important and far longer than the falling action, so the mountain-like diagram doesn't represent a story very well at all. But it's another attempt at grappling with what might be an overly difficult concept.

4. Why look at this stuff, anyway?

So I've presented simple definitions, and talked about older concepts that aren't strictly observed anymore. Why bother?

The answer is that these are the markers we use to analyze a story. And they can help us figure out why a story might be more or less satisfying, which is the ultimate analysis of why a movie was good or bad.While those "rules" aren't strictly required, the choices that authors make concerning them are all very interesting.

For example, you might watch a movie and realize that it doesn't contain the basic requirements for a story. For example, the conflict that arose in the beginning of the story might not be the conflict that is resolved in the end. Or a story might switch main characters halfway through the narrative.

A very skillful author might get away with this and the story might still be a success, but if you come away with a nagging feeling of dissatisfaction, these are the first places you might check. And really that's the main reason for considering them at all. If a story likes to play fast and loose with the plot, if it tries to skim over characterization, those are warning signs. They don't mean that the story is doomed to failure, and authors take chances all the time with structure. But these are going to be some of the first places that we look.

Thursday, December 7, 2017

Story Structure

So, I've talked at length about story types and about how they shape and satisfy audience expectations, which is the craft of all storytelling. In essence, we are trying to get behind the question of why the audience finds certain stories to be satisfying while others leave them feeling unsatisfied, feeling disappointed.

We all know that feeling. The feeling you get when walking away from a movie like Suicide Squad and thinking, "I was really looking forward to it, and it was funny and exciting and had some great scenes in it. I loved Harley Quinn. Why was it such a lousy movie?"

Each of the individual elements seems strong, seem to be exactly what we want: characters, attitude, pyrotechnics, aerial hyjinks. By many standards, it was a successful film. But overall, the whole movie was lacking something that isn't revealed by close inspection. It requires a broader view.

What we're missing is what is delivered by the storyteller's art. The art of the story is about creating narrative elements and weaving them together in a way that creates a larger meaning. It takes disparate elements and relates them to one another. Then it makes those relationships meaningful. Then it takes those meaningful relationships and arranges them in a coherent shape. These relationships, and the resulting shape is what we call story structure.

Trying to explicitly describe coherence is awkward, but its what critics mean when they refer to story arcs, character arcs, story seeds and payoffs. We talk about flat or two dimensional characters all the time, characters that do one thing and only one, and who never change or improve or expand during the course of the story. A story cannot consist of a string of random and unrelated events. By definition, it has to do more than that; it has to engage with a conflict and hammer out a resolution

One such attempt was made by Joseph Campbell in his book Hero with a Thousand Faces. It is an effort to describe why some stories feel more satisfying, resonate more with the audience than others. Campbell suggests that the Hero's Journey is a unifying story structure that brings complex elements together in a narrative circle. Campbell asserted that this structure was universal in that it was found in stories from many different cultures, and often found in the most fundamental culture-defining myths of those cultures.

In a sense, Campbell starts by claiming that these stories are what audiences find satisfying. Whether or not modern critics want them to embrace them, their universal presence, the fact that cultures return to them again and again from Biblical stories of David in 1025 BC to 11th C. Russian folktales to modern Hollywood movies, reflects the fact that there is something about hero's journeys that are compelling and satisfying. So for example, he doesn't assert that we ought to find these narrative elements meaningful for some reason that he articulates. Instead he demonstrates that we do find these elements meaningful and then speculates as to why that might be. Having first demonstrated their omnipresence, Campbell then goes further to try to explain what he thinks is behind their appeal.

However, the Hero's Journey is by no means the only attempt to define this kind of structure. Hollywood screenwriters have made multiple attempts at codifying a magic structure that will sell movies to producers, and presumably the audience. For example Save the Cat narrows down all screenwriting to 10 basic story lines, and gives the important elements of each. Similarly Something Startling Happens reduces all successful movies to 120 moments, or beats that have to happen in order for the audience to remain engaged.

The problem with all such screenwriting aids is that they can often deliver structure without substance, such as with Suicide Squad mentioned above. When structure is entirely divorced from narrative meaning, you get the equivalent of a Monty Python skit where a clown wanders through a medieval village because we need something startling to happen. Similarly, the criticism of the Hero's Journey is that it creates stories that are predictable and audiences feel that there is only one way for the story to progress. Narrative First says that insisting on rigid structure "imposes story-telling conceits upon a writer’s personal expression." And yet, we very often find that writer's personal expression is itself unsatisfying. The writer's need to speak doesn't mean that what he has to say is meaningful.

I think the answer is that the Hero's Journey represents one successful pathway to creating a satisfying story, though perhaps not the only pathway.

We all know that feeling. The feeling you get when walking away from a movie like Suicide Squad and thinking, "I was really looking forward to it, and it was funny and exciting and had some great scenes in it. I loved Harley Quinn. Why was it such a lousy movie?"

Each of the individual elements seems strong, seem to be exactly what we want: characters, attitude, pyrotechnics, aerial hyjinks. By many standards, it was a successful film. But overall, the whole movie was lacking something that isn't revealed by close inspection. It requires a broader view.

What we're missing is what is delivered by the storyteller's art. The art of the story is about creating narrative elements and weaving them together in a way that creates a larger meaning. It takes disparate elements and relates them to one another. Then it makes those relationships meaningful. Then it takes those meaningful relationships and arranges them in a coherent shape. These relationships, and the resulting shape is what we call story structure.

Trying to explicitly describe coherence is awkward, but its what critics mean when they refer to story arcs, character arcs, story seeds and payoffs. We talk about flat or two dimensional characters all the time, characters that do one thing and only one, and who never change or improve or expand during the course of the story. A story cannot consist of a string of random and unrelated events. By definition, it has to do more than that; it has to engage with a conflict and hammer out a resolution

One such attempt was made by Joseph Campbell in his book Hero with a Thousand Faces. It is an effort to describe why some stories feel more satisfying, resonate more with the audience than others. Campbell suggests that the Hero's Journey is a unifying story structure that brings complex elements together in a narrative circle. Campbell asserted that this structure was universal in that it was found in stories from many different cultures, and often found in the most fundamental culture-defining myths of those cultures.

In a sense, Campbell starts by claiming that these stories are what audiences find satisfying. Whether or not modern critics want them to embrace them, their universal presence, the fact that cultures return to them again and again from Biblical stories of David in 1025 BC to 11th C. Russian folktales to modern Hollywood movies, reflects the fact that there is something about hero's journeys that are compelling and satisfying. So for example, he doesn't assert that we ought to find these narrative elements meaningful for some reason that he articulates. Instead he demonstrates that we do find these elements meaningful and then speculates as to why that might be. Having first demonstrated their omnipresence, Campbell then goes further to try to explain what he thinks is behind their appeal.

However, the Hero's Journey is by no means the only attempt to define this kind of structure. Hollywood screenwriters have made multiple attempts at codifying a magic structure that will sell movies to producers, and presumably the audience. For example Save the Cat narrows down all screenwriting to 10 basic story lines, and gives the important elements of each. Similarly Something Startling Happens reduces all successful movies to 120 moments, or beats that have to happen in order for the audience to remain engaged.

The problem with all such screenwriting aids is that they can often deliver structure without substance, such as with Suicide Squad mentioned above. When structure is entirely divorced from narrative meaning, you get the equivalent of a Monty Python skit where a clown wanders through a medieval village because we need something startling to happen. Similarly, the criticism of the Hero's Journey is that it creates stories that are predictable and audiences feel that there is only one way for the story to progress. Narrative First says that insisting on rigid structure "imposes story-telling conceits upon a writer’s personal expression." And yet, we very often find that writer's personal expression is itself unsatisfying. The writer's need to speak doesn't mean that what he has to say is meaningful.

I think the answer is that the Hero's Journey represents one successful pathway to creating a satisfying story, though perhaps not the only pathway.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)